The second part of a two part article on the fall of the House of Desmond and the apocalyptic destruction of the old order in Munster. See Part I here. BY John Dorney

In May 1570, during the first Desmond Rebellion, several Irish lords had written to the Catholic Bishop of Cashel, desiring their pleas for military aid to be sent to Phillip II of Spain against, ‘The English, our bitterest foes’.

‘No pledge’, they write, ‘can make us believe or trust such foes… The English attack people in times of peace’ They urgently wished the King of Spain to know of ‘the sufferings we endure day and night the cruel war they are waging against, so that he may defend and preserve us’.[1]

And so it was that the Second, far more bloody and destructive Desmond Rebellion was sparked by intervention from Catholic Europe. Not as it happened, from Phillip of Spain, but from Pope Gregory XIII and the instigator of the first Desmond Rebellion (1569-73) James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald.

James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald landed at Dingle in July 1579 proclaiming Holy War against the Elizabethan English state.

The Annals of the Four Masters recorded that in July 1579,

James, the son of Maurice Dubh, son of John, son of Thomas, son of the Earl of Desmond, returned from France; and it was rumoured that he had comewith a greater number of ships than was really the case. He landed at Oilen-an-Oir, contiguous to Daingean-Ui-Chuis [Dangan in the Dingle peninsula], in Kerry.[2]

When he landed at Dingle, Fitzmaurice had with him about 100 Irish, Spanish and Italian soldiers and Papal banner and Papal emissary Nicholas Sanders. They read a proclamation from the Pope stating that Elizabeth I of England was ‘a tyrant’ and that her Kingdoms were forfeit.[3]

Whereas the first Desmond rebellion could be written off as an aristocratic revolt of the Fitzgeralds of Desmond against the Crown or as part of the feud of the Fitzgeralds (or Geraldines) against the Butlers of Ormonde, from an early stage, it was clear that this would be a much more serious affair.

This was a religious and ideological war on the part of many of the rebels as well as an attempt to conserve the power of the house of Desmond. It would also consciously try to rally various elements of indigenous Irish society against the ongoing English conquest of the island.

The background to the rebellion

The first Desmond rebellion had been a bloody and bitter affair, but it had ended in compromise, with the release of the Earl of Desmond and his brother John from captivity and the restoration of them to their lands.

Throughout the later 1570s, the English authorities in Munster painstakingly tried to construct what they considered to be a new ‘civilised’ order there. As well as outlawing elements of Irish culture, including the keeping Irish language poets and dressing in the native style and hanging up to 700 ‘masterless’ native mercenaries,[4] they devised a system whereby the Earl of Desmond and other lords would give up their private armies pay rent to the Crown and draw from their vassals, instead of military service, cash rent.

The Earl of Desmond appeared to be amenable to the English order in Munster but many of his followers were not.

The province would then, the theory went, become ripe for the introduction of English civilization. In late 1578, the Earl agreed to reduce his own armed forces to mere bodyguard of 20 horsemen. [5]

The Ealr himself may have accepted such terms but there were many of the Fitzgerald dynasty (especially the Earl’s brother John, widely considered the strongman of the family) who were deeply unhappy with becoming simply landlords.

There was also a wide constituency of others left out in the cold by the proposed new order. The traditional bardic classes would be left destitute as would professional soldiers. Many Gaelic lords feared confiscation at the hands of rapacious English settlers. And of course there was the question of religion. Most native Irish were Catholics, while the Kingdom of England was becoming more deeply and viscerally Protestant as the century went on.

So despite the smallness of Fitzmaurice’s ‘invasion’ at Dingle, despite his own low standing among the Geraldines (he had no lands and few followers) and despite the remoteness of the spot where he landed, most of Munster was soon engulfed in rebellion.

The Outbreak of the Rebellion

John of Desmond, the most powerful man in the dynasty after the Earl, was the first important figure to join with Fitzmaurice, which he did by assassinating and beheading two English officials – Henry Davells and Arthur Carte in their beds at an Inn in Tralee.[6]

He went on to occupy a number of strategic sites such as Carrigafoyle and Askeaton castles and to rally important families including O’Sullivan Beare, Roche and Barry to the rebellion. By the autumn of 1579 the rebels’ strength, bolstered by hired Gallowglass mercenaries, was estimated at about 2,000 men. By way of comparison, in all of Ireland there were no more than 1,200 English royal troops, though they could also count on the levies of Irish lords allied to the government.[7]

James Fitzmaurice was killed late 1579 in a skirmish with Burkes of Connacht, while crossing into their territory to steal horses, but in November of that year the rebellion secured a far more prestigious leader, Gerald, the Earl of Desmond himself.

Earl Gerald of Desmond joined the rebellion by sacking the town of Youghal in November 1579.

Desmond had tried to stay out of the rebellion and had assured the English officials Drury – the Lord Deputy – and Nicholas Malby that he had no knowledge of Fitzmaurice’s landing. According to English sources, he was proclaimed a traitor only after repeatedly refusing to surrender the Fitzgerald castles to English troops. According to the Irish Annals however, it was an English breach of faith that sent the Earl into rebellion;

He delivered up to the Lord Justice his only son and heir, as a hostage, to ensure his loyalty and fidelity to the crown of England. A promise was thereupon given to the Earl that his territory should not be plundered in future; but, although this promise was given, it was not kept, for his people and cattle were destroyed, and his corn and edifices burned.[8]

The Earl marked his declaration of war by sacking and looting the town of Youghal, while MacCarthy Mor did likewise to Kinsale. At Youghal, the Annals record;

The Geraldines seized upon all the riches they found in this town, excepting such gold and silver as the merchants and burgesses had sent away in ships before the town was taken. Many a poor, indigent person became rich and affluent by the spoils of this town. The Geraldines levelled the wall of the town, and broke down its courts and castles, and its buildings of stone and wood, so that it was not habitable for some time afterwards. .”[9]

Notably, though the rebel forces looted the town and killed the garrison, the English believed that the civilian population had helped them enter and English forces later hanged the mayor for treachery.[10]

From Newcastle West, the strongly fortified tradition seat of the Earldom, Gerald wrote to Irish lords around the country, imploring them to join his cause in the name of religion and their own interests;

“My well beloved friend… I and my brethren are entered into defence of the Catholic faith and the overthrow of our country by Englishmen which had overthrown our Holy faith and go about to overrun our country and to make it their own and to make us their bond men. We took this matter in hand with great authority both from the Pope’s Holiness and King Phillip [of Spain][11]

Reaction in Ireland was mixed. The Annals present the rebellion as a private war of the Geraldines against ‘their sovereign’ rather than primarily a religious or patriotic venture and most Irish lordships and clans in Munster lined up on the side of their factional interests (for or against the Fitzgeralds) rather than on any ideology. In particular, the most effective and committed enemies of the rebellion were probably the Butlers of Ormonde, the Geraldines’ long-time rivals.

English Response

Nevertheless, the English military response was predictably ferocious. The Lord Chancellor ordered the mustering of all able bodied men to defend the English Pale around Dublin and ordered the execution of all, ‘harpers, bards, rhymers and loose idle people with no master’.[12]

Nevertheless, the English military response was predictably ferocious. The Lord Chancellor ordered the mustering of all able bodied men to defend the English Pale around Dublin and ordered the execution of all, ‘harpers, bards, rhymers and loose idle people with no master’.[12]

The type of warfare that ensued was not characterized by pitched battle between large forces. Though the Annals and other contemporary sources do record some engagements between relatively large bodies (of up to 600 to 1,000 men) on either side, these were usually relatively fleeting and indecisive.

Rather, the conflict was in essence a guerrilla affair. The Geraldines and their allies controlled, apart from a small fertile area in County Limerick, secured by castles, a swathe of hilly country from north Kerry, through the Glen of Aherlow in Tipperary to west Waterford and from these remote bases, they raided incessantly the English and their allies.

The English strategy was firstly to take the Geraldine’s strongpoints which defended their fertile lowland country of modern county Limerick. This they largely succeeded in doing in early 1580, bringing up heavy guns by sea and bombarding Carrigafoyle Castle into surrender. The English proceeded to hang its Irish and Spanish garrison and thus terrorized the nearby castles of Askeaton, Newcastle West and others into abandoning their positions.[13]

‘They killed blind and feeble men, women, boys, and girls, sick persons, idiots, and old people’ Annals of the Four Masters on English tactics.

English troops led by Pelham and Malby as well as the Earl of Ormonde and his levies (together about 2,000 troops) then marched through marched through the Fitzgerald’s lands, destroying their means to make war –burning their crops seizing their cattle and killing their tenants. Without this economic base the Fitzgeralds and their allies were helpless to feed or to pay their soldiers.

Much the same logic applied to the rebels’ tactics, which were aimed not so much at defeating the Crown forces in battle as taking way their means to subsist and garrison the country. As the Annals of the Four Master explain,

The sons of the Earl proceeded to destroy, demolish, burn, and completely consume every fortress, town, corn-field, and habitation between those places to which they came, lest the English might get possession of them, and dwell in them;

Similarly

the English consigned to a like destruction every house and habitation, and every rick and stack of corn, to which they came, to injure the Geraldines, so that between them the country was left one levelled plain, without corn or edifices.

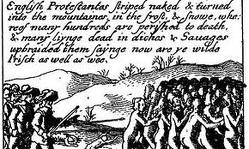

So in many ways the conduct of the two sides was fundamentally similar, both preying on non-combatants, burning crops and seizing livestock. But the Annals noted a special ruthlessness about the conduct of the English towards the civilian population;

These, wheresoever they passed, shewed mercy neither to the strong nor the weak. It was not wonderful [surprising] that they should kill men fit for action, but they killed blind and feeble men, women, boys, and girls, sick persons, idiots, and old people.[14]

It is difficult to conclude other than that the English introduced a new level of brutality into 16th century Irish warfare with the wholesale killing of civlians nad use of unrestricted scorched earth warfare. The English poet and colonist Edmund Spenser, who fought in the Desmond War, was explicit that the tactics used were designed to decimate the civilian population and starve the rebels into surrender;

“Towns there are none of which he may get spoil, they are all burnt; Country houses and farmers there are none, they be all fled; bread he hath none, he ploughed not in summer; flesh [livestock] he hath, but if he kill it in winter, he shall want milk in summer, and shortly want life. Therefore if they be well followed but one winter, ye shall have little work to do with them the next summer. …

All those subjects which border upon those parts, are whither to be removed and drawn away, or likewise to be spoiled, that the enemy may find no succour thereby: for what the soldier spares the rebel will surely spoil”. “The end I assure you will be very short’[15]

The end though, was not in fact short at all in coming. English troops could not in practice plunder at will throughout the countryside, for they were vulnerable to ambushes and could only raid relatively compact areas in large numbers. The rebellion was also given a new lease of life in mid 1580 when it was joined by a Pale Lord Viscount Baltinglass and a veteran Gaelic raider, Fiach MacHugh O’Byrne of the Wicklow Mountains, who together mauled an English force under the new Lord Deputy, Grey at Glenmalure in August of that year.[16]

Perhaps chastened by his humiliating defeat, Grey dismissed some peace feelers the Earl of Desmond had sent out through his wife Countess Eleanor[17] and instead stepped up English scorched earth tactics. Such was his reputation for cruelty that he was reviled even within the English Pale as, ‘a bloody man who regarded his subjects’ lives not more than dogs’[18]

The end of the war was not seen for four tortuous years, during which tens of thousands would die, killed directly by violence and by resulting famine and plague.

Smerwick

Ireland was only one of many countries wracked by internal conflict in late 16ht century Europe. In France, civil wars raged between Catholic and Protestant. In the Netherlands the mostly Calvinist Dutch bitterly resited their erstwhile overlords, the Catholic Spaniards’ re-conquest of the Low Countries. And Ireland too in September 1580 became a battleground in these European wars of religion.

Pope Gregory XIII had backed James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald since the early 1570s, when he fled first to France and then to Rome after his defeat in the first Desmond Rebellion. In Irlenad Fitzmaurice had been wandering swordsman but the Pope granted him men, money and the title of Marquess of Leinster in order to fight for the Catholic cause in Ireland.[19]

In 1580, after Fitzmaurice’s death, the Pope, unhappy with Phillip of Spain’s truce with the Dutch Protestant rebels, pressurized Phillip to invade Ireland as a means of ultimately invading and re-Catholicizing England. While he could not get the Spanish king to launch his own expedition to Ireland, he did get Phillip to agree to provide ships to transport about 800 mostly Italian volunteers, who had been recruited and paid for by the Papacy, to Ireland to aid the rebellion there in September of 1580.[20]

About 700 Papal troops landed at Smerwick in September 1581 but were besieged taken prisoner and then massacred by the English.

The Catholic expedition landed at Smerwick in Dingle on the 10th of September 1580. The Geraldine forces were however slow to help them and soon the Catholic soldiers were besieged in a fort at Dun an Oir by land forces under Grey and a fleet under William Winter. Under a terrible artillery bombardment their commander Sebastiano di San Giuseppe surrendered to Grey on November 10th, ‘their ensigns [flags] trailing’. Grey first made sure they were disarmed and then had the surviving 600 soldiers as well as a number of priests and local civilians ‘put to the sword’.[21]

Grey later argued that, as they had been sent, not by the King of Spain but by the Pope they were not entitled to the rights of quarter granted to soldiers serving under a lawful sovereign. Elizabeth I, for her part extended her thanks to her troops. [22]

It was the largest single massacre of the Desmond wars, the end of any prospect of continental help for the rebels one of the factors that ultimately led to renewed war between England and Spain.

The bitter end

The war in Munster dragged on through 1581 with much bloodshed but no decision. The rebellion in Leinster collapsed early in the year, it leader Baltinglass fled to France and in May 1581 many Munster lords submitted for pardon. For the heads of the Desmond Earldom though, there would be no terms of surrender – they were specifically excluded from the terms of a General Pardon granted to other rebels.

And so the war went on. The Annals noted that, that John of Desmond, raiding from the Glen of Aherlow plundered the Butler’s country in Laois, and their towns around the Suir river, as well as MacCarthy Mor (who had submitted)’s country (in modern west Cork) while the Earl similarly concentrated on; cutting down of the Butlers by day and night, in revenge of the injuries which the Earl of Ormond had up to that time committed against the Geraldines.[23]

The English forces, at their peak 6,400 strong were too expensive to maintain and had to be drastically cut, to 3,000 in the cours of 1581, but this was not enough to contain the Geraldine guerrillas or to maintain security outside of fortified garrisons.

In early 1582, John of Desmond was killed in an ambush laid by English troops under a captain Suitsi while crossing the river Avonmore – his body was quartered and his head sent to Grey.

The greatest number of casualties however were among what one English official described as, ‘the poor people who live only upon their labour and fed by their milch cows’.

They were regularly killed in reprisals but famine and disease by 1582 was taking a much higher toll among them. In the first six months of 1582 it was reported that some 30,000 people had died of starvation and disease in Munster. Warhame St Leger reported that Munster, ‘is nearly unpeopled by the murders done by the rebels and the killings by the soldiers.’ [24]

[pullquote]By 1582, tens of thousands of deaths by famine were were being reported in Munster.[/pullquote]

The Annals report, “the whole tract of country from Waterford to Lothra, and from Cnamhchoill to the county of Kilkenny, was suffered to remain one surface of weeds and waste.’

Edmund Spenser for his part graphically described the effects of the scorched earth warfare he advocated;

“in those late wars in Munster; for notwithstanding that the same was a most rich and plentiful country, full of corn and cattle, that you would have thought they could have been able to stand long, yet eare one year and a half they were brought to such wretchedness, as that any stony heart would have rued the same.

He described starving figures emerging from the remote places where they had hidden;

Out of every corner of the wood and glens they came creeping forth upon their hands, for their legs could not bear them; they looked Anatomies [of] death, they spoke like ghosts, crying out of their graves; they did eat of the carrions, happy where they could find them, yea, and one another soon after, in so much as the very carcasses they spared not to scrape out of their graves;

He concluded;

A most populous and plentiful country suddenly left void of man or beast”.[25]

Grey’s brutality might have been forgiven had he been more successful. As it was, he was replaced by Elizabeth as commander of English forces in December 1582 by Thomas Butler the Earl of Ormonde – hereditary enemy of the Geraldines.

With a mobile force of about 1,000 and making skilful use of local allies, he drove the Geraldines out of the Waterford/Tipperary area and into the hills of Kerry. The MacCarthy Reagh clan for instance along with some English soldiers reported they had driven the Earl, ‘into his own waste country’ where his troops could find no provisions and deserted. They also claimed credit for the killing of Gorey MacSweeney and Morrice Roe, two of Desmond’s gallowglass captains.[26]

By September 1583, Desmond’s forces had been reduced by casualties and surrenders from a high of 2,000 to mere handful. Important members of his own dynasty such as the Sensechal of Imolky and even his wife Eleanor came in to surrender.[27]

The Earl’s end when it came, was inglorious in the extreme. Hiding in a remote valley named Glenagenty, near Tralee, he was surprised by a party of the local clan the O’Moriartys, who found Desmond alone and wounded in a poor cabin. Although he begged for his life, they killed and then beheaded him. His head sent to Queen Elizabeth. His body was triumphantly displayed on the walls of Cork.

The Desmond dynasty had both literally and figuratively, been decapitated. The war was finally over. As much as a third of the population of Munster is thought to have died.

The Four Master conclude that in 1584;

A general peace was proclaimed throughout all Ireland, and the two provinces of Munster in particular, after the decapitation of the Earl of Desmond, of which we have already made mention. In consequence of this proclamation, the inhabitants of the neighbouring cantreds crowded in to inhabit Hy-Connello, Kerry, and the county of Limerick.[28]

[pullquote]The Earl of Desmond was killed by the O’Moriarty clan in November 1583 and his head sent to Elizabeth I.[/pullquote]

Fertile places such as county Limerick recovered relatively quickly. By 1587, the Solicitor General Roger Wilbraham reported that ‘this is a most plentiful year of corn…[there are] five times a many Irish inhabiting in the county of Limerick as were within these two years’. He urged the settling of more English planters there before all the land was re-occupied by the Irish[29]. On the other hand another settler William Herbert reported the following year that, ‘this province’s waste and desolate parts…[are] by reason of the calamities of the late wars, void of people to manure and occupy the same’[30].

Assessing the Desmond wars

How should we assess the Desmond rebellions?

Were they merely the resistance of a local feudal lordship to a centralizing state? There is certainly much truth in this, the Annals of the Four Masters for instance, normally vociferous in their support for Irish Catholic causes, did not take the Fitzgerald’s rebellion seriously in this regards, rather they concluded, citing the Desmond dynasty’s English origins back in the twelfth century;

‘It was no wonder that the vengeance of God should exterminate the Geraldines for their opposition to their Sovereign, whose predecessors had granted to their ancestors as patrimonial lands’.

The Desmond wars were in part a feudal revolt in part a religious war and in part a resistance to colonisation.

We should not forget also that the Desmond rebellions were sparked in the first place, in 1569, by the armed rivalry between the Ormonde and Desmond lordships. And it was ‘Black Tom Butler’, Earl of Ormonde who ultimately brought the rebellion to an end.

For the English the rebellion was about destroying ‘degenerate’ militarized Irish lordships that preyed on their own tenants and replacing them, in theory if not always in practice, with the rule of law.

But it also clear that the Desmond rebellion were perceived on both England and Irish sides as an ethnic war. One of the first targets of the Geraldines had been the nascent English colonies in Munster and it id difficult to imagine the extreme brutality English forces displayed towards non-combatants had they not regarded they Gaelic Irish as an alien and uncivilized people.

The Desmond rebellion was also followed by the Munster plantation – an attempt to introduce thousands of new English settlers into the confiscated Fitzgerald lands. Some, 500,000 acres were planted with English colonists and by 1589 there were up to 3-4,000 English settlers in the province[31].

Finally also of grim importance for the future was the religious dimension. The Catholic Church recognized a number of those hanged during the rebellion as martyrs.[32] Significantly, many of these were not from the Munster Gaelic heartland of the revolt but from anglicized areas such as Dublin city and south Wexford. In January 1581, for example 45 citizens of Dublin were hanged early in the year for treason, some of them going to their deaths as Catholic martyrs, proclaiming their faith.[33]

If the Desmond Rebellion cannot be said to have been a nationalist struggle – a coherent Irish national and religious identity was arguably still unformed, it can perhaps be said to be one of the seminal events that led to its creation.

A generation later, another Irish war lord, Hugh O’Neill of Tyrone would much more successfully claim that he was fighting the English for ‘faith and fatherland’ with military aid from the Kingdom of Spain itself.

References

[1] Cyril Falls, Elizabeth’s Irish Wars, p139

[2] Annals of the Four Masters, online here.

[3] Falls p 126

[4] Colm Lennon, Sixteenth Century Ireland the Incomplete Conquest, p216

[5] Lennon, p221

[6] Falls p127

[7] For the impact of John’s joining of the rebellion, Lennon p 223 and estimate of insurgent strength, Falls p128

[8] Annals of the Four Masters

[9] Annals of the Four Masters

[10] Falls p 130

[11] Cited Anthony McCormack, The Earldom of Desmond, Decline and Crisis of a Feudal Lordship, p

[12] Falls p 127

[13] Lennon p225

[14] Annals of the Four Masters

[15] Edmund Spenser, a View on the Present State of Ireland, online here.

[16] Lennon, p 225

[17] Falls p135

[18] Lennon, p227

[19] Falls p 126

[20] Geoffrey Parker, Imprudent King, A New Life of Phillip II, p 272-273

[21] Vincent Carey, Grey, Spenser and the Slaughter at Smerwick, in The Age of Atrocity, Violence and Political Conflict in Early Modern Ireland, p83-86

[22] Ibid, p91-92

[23] Annals of the Four Masters

[24] Lennon, p227

[25] Spenser, View

[26] Florence McCarthy to Burghley, 29 November 1594, Daniel McCarthy, Letter Book of Florence McCarthy Reagh, Tanist of Carberry, p.121.

[27] Lennon p228

[28] Annals of the Four Masters

[29] Wilbraham to Lords Commission for Munster Causes, September 11, 1587, CSP 1586-1588 pp. 405-406

[30] Herbert to Burghley June 1588, Ibid. p532

[31] Nicholas Canny, Making Ireland British p154-155

[32] They were Bishop Patrick O’Healy and Father Cornelius O’Rourke, Franciscans: tortured and hanged at Kilmallock 22nd August 1579

- The Wexford Martyrs: Matthew Lambert and sailors – Robert Tyler, Edward Cheevers and Patrick Cavanagh: died in Wexford 1581

- Bishop Dermot O’Hurley: tortured and hanged at Hoggen Green (now College Green), Dublin, 20th June 1584

- Margaret Ball: lay woman, died in prison 1584

- Maurice Kenraghty (or MacEnraghty): secular priest, hanged at Clonmel on 20th April 1585

[33] Annals of the Four Masters.